Get Weird Again

Ricardo Curtis on Why the Future of Animation Needs Risk, Roots, and Reinvention

Since the release of my video essay back in April on the state of jobs in animation and visual effects, several people have mentioned to me its core recommendation: “Get weird again”. The statement was meant to bring Canadian animation back to its roots of experimentation and chance-taking, and that today the most likely place one would find that is on independent distribution channels like YouTube and TikTok.

Credit to Ricardo Curtis, co-founder of House of Cool, for helping me make this connection. Back in January, I was invited to join a few friends for New Year’s brunch, including Ricardo, Kate Moo King-Curtis, and Lillian Chan. We bantered around what the industry was like these days: Lillian commented on the drop in new shows geared towards teens as a result of YouTube capturing their attention; Kate talked about the need to preserve the role of the artist in the face of AI; and Ricardo talked about the difference between the current industrial model and Canadian TV’s early days of made-up shows created to fill air time, how weird some of these shows were, and the foundation they created for the future.

“We need to get weird again,” I thought.

A few months later, I asked Ricardo to continue the conversation to share more of his experience and insight. The Toronto‑raised, Jamaican‑born artist and studio co-founder is a distinguished animator, story artist, and director whose career spans iconic hits like The Iron Giant, Monsters, Inc., The Incredibles, and The Book of Life. He recently co‑directed the animated comedy‑horror Night of the Zoopocalypse. As Co-Founder and now Co‑General Manager and Creative Director of Toronto’s House of Cool, Ricardo’s style, blending classic animation storytelling with genre‑bending projects, continues to give him an important perspective on where the field is headed.

Here are highlights of our conversation.

MJ: How would you describe the current state of the animation industry?

RC: The way the industry is structured, it’s making it very difficult, in my opinion, for the industry to grow in a way that's healthy, because fewer and fewer people are making decisions. From a business sense, it used to be that on one side, we had platforms: broadcast and cable, DVD and video, theatrical, free TV. On the other side, there were IP holders: the people who owned the content. And then in the middle, there was this huge ecosystem of studios of various sizes, there were distributors, producers, there were sales agents, just a ton that happened in the middle.

Because of streaming and consolidation, today we basically have Netflix, a couple other streamers who are smaller than Netflix, we have theatrical, which is not growing, and we have linear broadcast. For animation, broadcast is still huge, but it’s not growing. These platforms have been just taking over more and more and more. Now the platforms now own a lot of IP, and if they don’t own the IP, they can control the IP. There’s no distribution and sales happening in the middle because now they’re doing distribution and sales.

If I were to make an analogy of it, it's kind of like, bananas. We eat a certain type of banana today only because we always ate another type of banana that all died because of a banana blight. But we don't know that. And the problem is that once you reduce the number of companies and people that are in control, it opens you up to being wiped out by one single event. And I feel that's kind of where we are in animation now -- or at least getting to that point where animation and the industry can be wiped out, or majorly disrupted, by a single event, a single technology, a single decision.

MJ: I think you're the first person I know that has taken the comparison of people saying the industry is bananas and actually been able to literally interpret that.

MJ: Can you recap your observations on the early days of Canadian television and how they laid the foundation for what was to come?

RC: What was great about Canada, and in our area in particular, the Toronto/Ontario region, was that we were exposed to so many interesting things. I’m talking about the 1970s and 80s. So many interesting things, because channels, stations, broadcasters didn’t really know what they were doing. They didn’t really know what the audience wanted. They knew they had this thing called television. You could make content, but nobody knew what anyone in particular really wanted unless you put it out there and it caught fire.

There were a limited amount of channels, and only so much airtime. It was mostly live action and news, sports, and whatnot. And occasionally there would be some animation, but it was pretty limited. We often watched a lot of anime because it was cheap to acquire. We were watching Astro Boy and Speed Racer.

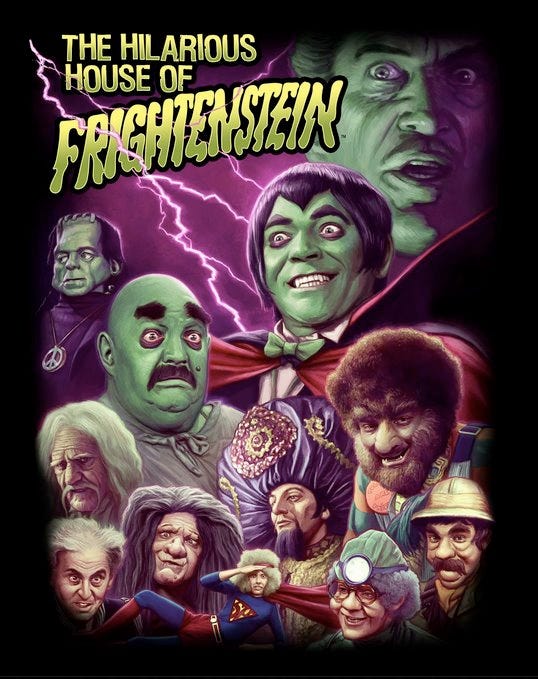

There were also local channels, and what was great about the local channels was that it was very particular for a region. They would make stuff as far as their licenses would allow them to broadcast, which usually wasn’t that far. And these channels didn’t have any money. But we could make our own content. And it left this ability for people who were creative just to make stuff. And the stuff was crazy. The Hilarious House of Frightenstein, if anyone has ever seen that thing, it’s absolutely nuts. It makes, like, zero sense, but it was awesome. We had The Red Green Show, we had Mr. Dressup, which inspired Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood. We had You Can’t Do That on Television, which was the backbone that created Nickelodeon.

All these things were created by people who had basically no rules, no money. And they just used their smarts and gumption to just make something and see what happened. Of course, most of them were dead on arrival. But a few of them survived, and they became something.

MJ: What’s your view on the role of independent platforms like YouTube for the future of animation?

RC: YouTube has won the eyeball war hands down. You can put anything on YouTube, essentially, as high or low quality as you want. And you may or may not find an audience, but you can get it out there. When I’m talking to students or younger people trying to enter the industry, the first thing that I say is, “Don’t do what I did.” I did what I did because that’s what I knew, and it worked for me. You should do what you do because you know what you want, and you know best what works for you.

In September 2024, I went to this animation festival in Guadalajara, Mexico called Pixelatl. I was showing some early stuff from a film I had directed. It was great. There was this large theatre there and, one day I went, it was packed, standing room only. People were going crazy. It was all young people. I swear Taylor Swift must have been in there because they were just losing their minds. So I had to see what was going on. I went in, and there was one young woman talking [Vivienne Medrano]. I had never seen her before, but they were hanging off every word that she said. It turned out she had made this YouTube animated [show] called Hasbin Hotel. I’d never heard of it before, but it absolutely was just bonkers, the people were going nuts for it.

She made it on her own. It was her thing, and it caught on. Amazon bought the rights for it, and they’re now doing a series. I would have never done that, because that’s not me. I didn’t grow up like that, but for them, it is. She’s thirty years younger than me or probably more, and she found a way. She found her audience.

MJ: What about AI? Will it be a useful tool or further erode people’s ability to generate income?

RC: There’s an existential crisis of AI coming. We’re definitely seeing amazing AI tools doing a lot of really interesting things. I don’t think AI is really “there” yet, but it'll probably get there very quickly, where you can make good content with a limited number of people. If that happens, it means the cost and time that it takes to make animation will be reduced by many factors.

Somebody could make a short film or project about trans-elf woodworkers; they won’t have to attract ten million viewers for it to appeal to them. Maybe they only need to attract ten thousand viewers. And if that’s the case, that means all kinds of niches can open up. Instead of a thousand people working on one film, they can have ten people working on a hundred films. That could very well happen, and that would open it up for everybody, and potentially usher in a new golden age of animation.

If I were young, I would definitely keep my ear to the ground and just do what I think is great, what I think I would love, and maybe other people would love. Just do that, because it’s really difficult to predict what the future of this industry is going to be.

MJ: So, with all these changes, what do you think still holds up as a sustainability principle that has stood the test of time?

RC: I think one of the things I want to say is that I’m speaking from a place of privilege, right? I came in at a very good time in the industry. It blew up. So, it worked out well for me. The timing was amazing. It’s easy for me to say keep your ear to the ground, and keep your options open, and do what you want to do, and hopefully people will love it, and you’ll have great success with this industry. I totally understand that it’s much scarier for people who do not have a solid job, or are just coming out of school, or are just in school right now. All they see is change. All they hear about is bad news.

But my main takeaway is this: everybody wants to be entertained. We are in an industry where we deliver on that promise. We don’t have to do it in a way that historically is set to be done in a certain way. But the need for entertainment is not going to go away, ever.

If you keep that in mind, and if you think you have the ability to entertain, you should be able to find an audience -- if you are smart enough, if you’re good enough, if some luck runs your way, and if you’re tenacious enough. It can happen for you.

Great message for both the young filmmakers just starting out and professionals in between jobs. We have entered the Creator Universe and the DIY culture. this is the best of all possible times to be a creator.